Moffitt Experts Conduct First Analysis on New Criteria for Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a group of conditions caused by abnormal blood-forming cells in the bone marrow. Those with myelodysplastic syndromes don’t have enough healthy blood cells, which can lead to issues like anemia and uncontrollable bleeding.

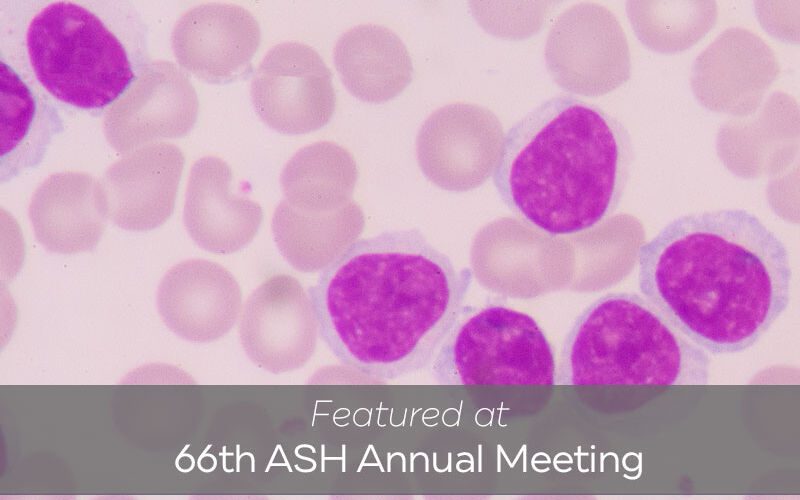

Another blood cancer that affects the bone marrow is called chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. In addition to lower blood counts, the bone marrow produces too many white blood cells called monocytes. The monocytes don’t fully develop and are unable to carry out their normal functions, like fighting off infections.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recently changed part of the criteria for diagnosing chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Previously, a patient needed to have a monocyte level of 1,000 and constitute 10% of all white blood cells or more for a chronic myelomonocytic leukemia diagnosis. Now, they need to have a monocyte level of 500 or more, as long as it makes up 10% of the total number of white blood cells.

Eric Padron, MD, an oncologist in Moffitt Cancer Center’s Malignant Hematology Department, has focused a significant amount of his work on chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and was part of the WHO committee that authored this change. “Due to this change, by default, the number of people with this disease is going to go up because the criteria is now more inclusive,” Padron said. “Questions have remained looking at patients that are now considered to have chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, such as how are these patients the same? How are they different? Are they similar to any other diseases?"

Eric Padron, MD

With these questions in mind, Padron and a team of specialists analyzed Moffitt’s database. “We looked at patients who were diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndromes when the criteria was stricter and now are said to have chronic myelomonocytic leukemia,” Padron said. “In that group of patients in which their disease has technically changed semantically, we looked at what disease they truly resembled more, the myelodysplastic syndromes or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia.”

In their study, Padron and his team found that patients who were switched to a chronic myelomonocytic leukemia diagnosis based on the new criteria more so resembled myelodysplastic syndromes genetically.

“Perhaps people will reconsider this new definition of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, and pathologists will still call it myelodysplastic syndromes using the traditional cutoffs versus what has been newly proposed because now the evidence suggests that the old criteria may be more appropriate,” Padron said.

According to Padron, this is one of the first analyses of data since the criteria for chronic myelomonocytic leukemia was changed. “Changes are OK, but we have to make them based on evidence and data, and there was limited evidence or data to support this change,” Padron said. “It was more so an expert consensus. What we originally predicted was going to happen (patients once considered to have myelodysplastic syndromes who are now considered to have chronic myelomonocytic leukemia would resemble chronic myelomonocytic leukemia more) turned out to be the opposite.”

Padron presented the findings at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting. As researchers wait for more studies to be done, they are working on finding other markers that could better identify patients who truly resemble chronic myelomonocytic leukemia.