Will COVID-19 Cause a Surge in Cancer Cases?

When COVID-19 swept through the U.S. in mid-March, cancer centers had to adapt to fight the deadly disease while protecting immunocompromised patients and frontline health care workers.

When it comes to cancer care, very little is elective, and even a pandemic cannot stop treatment. At Moffitt Cancer Center, telemedicine increased by more than 500% during the pandemic and the cancer center began performing in-house COVID-19 testing prior to certain surgeries and treatments.

Dr. Robert Keenan, Chief Medical Officer and Vice President of Quality

“There was a lot of virtual hand holding,” said Dr. Robert Keenan, chief medical officer and vice president of Quality. “We tried to put in place measures to create an environment that let patients know this was as safe a place as any to come for treatment.”

Clinic visits dropped as much as 50% during the peak of the pandemic, but volumes are now almost back to normal. New patient appointments were down about 40% and are now also trending back upwards.

There was little change in the number of patients receiving chemotherapy and radiation because many patients were mid-treatment when the pandemic hit, but Moffitt expects to see a slight drop in infusion and radiation volumes as those patients wrap up treatment.

But what about individuals who are not yet diagnosed?

Surveillance appointments, such as mammography and colonoscopies for average-risk patients, were postponed during the pandemic. Keenan says it’s too early to tell the potential impact the delay in screening will have when it comes to early detection of cancers. However, he does predict patients will be diagnosed with cancer at later stages, especially for cancers that don’t have routine screening like lung and head and neck cancers.

“People find these cancers because they have a problem and go see a primary care physician,” said Keenan. “During the pandemic, these patients may have ignored their symptoms or couldn’t get help because doctors weren’t seeing patients. There’s also an economic impact; people have lost their jobs and health insurance and feel they are unable to seek help. Those are the more important drivers to patients not being diagnosed as early as they could have been.”

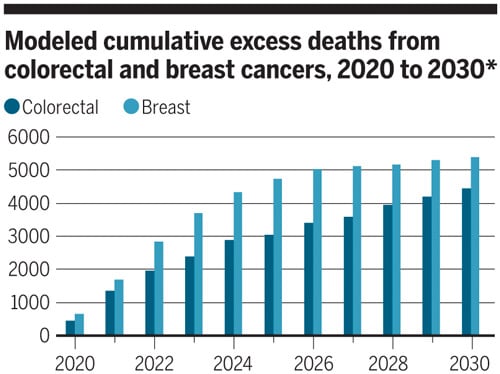

According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), there has been a steep drop in cancer diagnoses in the U.S., but there is no reason to believe the actual incidence of cancer has dropped. The NCI put together a rough model on the effect of COVID-19 on cancer screening for breast and colorectal cancer, which together account for about one-sixth of all cancer deaths. Based on the assumption screenings were stopped for only six months, the modeling suggests there will be almost 10,000 additional deaths from those two cancers on top of the expected 1 million in the next decade. The number of additional deaths per year is expected to peak in the next year or two. The analysis is conservative and does not consider other cancer types or account for cancers that haven’t been diagnosed yet.

Graphic Courtesy: Valerie Altounian, Science and the National Cancer Institute

The true impact COVID-19 will have on cancer diagnosis and deaths won’t be known for years to come, but there is no doubt there will be lasting effects.

Instead of focusing on the consequences of the pandemic, Keenan prefers to reframe the conversation to how COVID-19 has provided a catalyst to rethink health care. This could include breaking the tradition that all treatment and procedures have to be done in a hospital and that all appointments have to be conducted in-person.

“This is an opportunity for us to reevaluate a number of our processes on how we can do things in a better way that can also be more capable of withstanding some of the challenges that could come from COVID-19 or something like that in the future,” said Keenan.

As Florida continues to see a spike in COVID-19 cases, some community hospitals are facing hospitalization and intensive care unit challenges. A few have started to once again postpone elective surgeries. As of now, it has not affected operations at Moffitt.