A Lasting Legacy

Out to breakfast one morning, Fred Tallada was puzzled when his wife, Carolann, ordered multiple meals. Was she just very hungry? But when the food arrived, Carolann walked outside and brought it to a homeless man and his dog.

That’s just the kind of woman she was, Fred says.

Carolann worked as a teacher’s aide at Port Charlotte Middle School and was head of the school’s Sunshine Committee, a group tasked with spreading joy and offering support to teachers and staff.

If there was a school dance, she was there. If a friend needed money for groceries, she opened her wallet.

Carolann, already a breast cancer survivor, was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2020 at age 62. Even after years of treatment and a third cancer diagnosis of adrenal cancer, her spirit for generosity was strong. When she was given an opportunity to help other cancer patients, there was zero hesitation.

“Her doctor asked her if she would be willing to let them take her cancer out when she passed for studies, and of course she said, ‘Well, why not,’” Fred said.

‘For the Greater Good’

The Thoracic Oncology Department at Moffitt Cancer Center initiated its Rapid Tissue Donation Program in 2015. Rapid tissue donation is the donation of tissue — including primary tumors, metastases and noninvolved tissues — from patients who have died. A collaborative effort with Moffitt’s Pathology Department, which provides the facilities and manpower to perform the collections, the program gives researchers a unique opportunity to investigate cancer from a different perspective. It also enables patients to leave a lasting legacy to help future patients.

Studying tumors that have received treatment or metastasized can give a new glimpse into how cancer develops, why it becomes resistant to certain treatments and potentially help develop new therapies. Moffitt is one of the only centers in the region offering this type of program.

“People with cancer can’t donate their organs for transplantation in the usual way due to risk of transplanting cancer, so donating cancer tissue for research is an alternative for those who want to do something for the greater good,” said Theresa Boyle, MD, PhD, a pathologist who helped develop the program. “And for the researchers, it’s very rare to have access to this kind of post-therapy cancer tissue. We often don’t know what has caused the cancer to thwart therapy, and that is why the donated tissue is so valuable.”

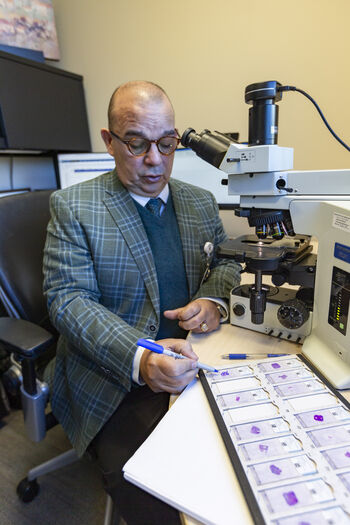

Pathologist Alex Lopez, MD, reviews slides with donated tissue samples and marks areas to be saved for research.

During a patient’s diagnosis and treatment, very little tissue is collected from biopsies, and most is used up by clinical testing. Rapid tissue donation after a patient’s death allows doctors and researchers to collect large amounts of tissue that can fuel multiple projects to investigate therapies, cancer biology, metastasis and how treatment can affect the rest of the body.

Since the program’s first year, 105 patients with lung cancer have consented to participate in the Rapid Tissue Donation Program and samples have been collected from 60 donors, leading to important discoveries. Researchers identified a gene fusion that may have developed as a resistance mechanism to ALK inhibitor therapy, a targeted treatment for non-small cell lung cancer. This finding emphasizes the importance of broad genetic testing to identify gene changes with the possibility of adapting therapy.

Using the donated tissue, researchers also discovered that the expression of PD-L1 — a protein that can be used as a biomarker to predict how a patient may respond to immunotherapy — can differ at different tumor sites in the same patient. This illustrates the need for caution and the importance of weighing multiple factors when considering immunotherapy.

Humberto Trejo Bittar, MD

“We are learning so much, not only about the therapies but also about cancer biology,” said Humberto Trejo Bittar, MD, director of Autopsy Service at Moffitt. “These things are important to look at: how cancer is different in different sites and individual metastases. Having the opportunity to learn this detail of cancer biology from a genomic and metabolic standpoint helps you test multiple different approaches.”

The program has now received a three-year, $1.5 million grant from the Florida Department of Health’s James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program to set up the infrastructure to expand beyond lung cancer.

“The Moffitt community of clinicians and researchers are going to guide which type of tissue we are going to target,” said Matthew Schabath, PhD, principal investigator of the James and Esther King Biomedical Research Grant and for Total Cancer Care, the Moffitt program that oversees biospecimen collection and how they are used in research. “We have an idea of a few populations outside of lung cancer, but we want our clinicians and researchers to tell us what they need from us.”

Matthew Schabath, PhD

Future research may expand from disease-specific studies to groups of patients with certain genetic mutations such as KRAS G12C, which can occur in multiple cancer types; groups with metastatic cancers to the brain; or nonsmokers with biomarkers that may span to different cancer types.

A collaborative goal of the grant is to develop a toolkit for other institutions to set up their own rapid tissue donation programs.

“What is really important is that we develop this to be successful at Moffitt,” Schabath said. “We want to first really tailor this for Moffitt, and then our developed toolkit will be a starting point that can be adapted by other institutions.”

‘I Always Win’

Like Carolann Tallada, Laurie Seligman was being treated for lung cancer at Moffitt when she heard about the Rapid Tissue Donation Program. She was diagnosed with stage 3 non-small cell lung cancer in 2018 at age 57. After being told her cancer was inoperable, she underwent chemotherapy and radiation where she was living in Texas. An immunotherapy treatment gave her a short remission, but her cancer returned. She pushed for more comprehensive genomic testing for more answers.

“I had to find out what was driving my cancer,” Seligman said.

Laurie Seligman hopes her donation will provide insight into non-small cell lung cancer and KRAS gene mutations.

That testing revealed Seligman has a KRAS mutation, a type of gene mutation that occurs in about 25% of non-small cell lung cancers and leads to treatment resistance and poor prognosis. The KRAS gene regulates cell growth and division, and when it is mutated, it signals cells to grow too much.

Seligman moved to Florida in 2021 to transfer her care to Moffitt. “I didn’t realize how sick I was. I had stopped being able to shower on my own. I couldn’t pack up the rest of my house because I was having trouble breathing and moving the boxes.”

The next few months were tough for Seligman. She underwent three procedures to remove fluid from the space between the lungs and battled pneumonitis. She spent more than three weeks hospitalized, one of those days on a ventilator, but was able to move to a rehabilitation floor and eventually home.

Seligman was too weak for chemotherapy, but in May 2021, the U.S Food and Drug Administration approved Lumakras, the first targeted therapy for lung cancer patients with a KRAS mutation. The treatment put Seligman into remission for a year. Her care team at Moffitt found a new combination of therapies to try when her cancer returned. Side effects caused a switch to a new line of chemotherapy in mid-2024, and her disease has been stable ever since.

During Seligman’s treatment, a fellow patient told her about the Rapid Tissue Donation Program. She immediately asked to join.

“I was an organ donor, and I can’t donate anymore. This is what I can do,” Seligman said “When I die, I don’t need my body anymore. I can help the next generation help kill cancer.”

Just as fighting for more genetic testing unlocked a new treatment option for her, Seligman hopes her tissue provides even more insight into her disease and KRAS mutations. Having a genetically driven cancer that has received multiple different treatments makes her tissue extra valuable, she jokes.

“In the end, I win. I always win,” she said. “When I die, guess who else dies? My cancer. My body will go to Moffitt, and they will take my tissue and use it for research against it. So even after I am dead, I am still winning.”

The Donation

Although some patients, like Seligman, hear about the program through word of mouth, many come to the program through Gina Nazario.

In 2020, Nazario became the project manager for the Rapid Tissue Donation Program, with the goal of not only growing the program, but also creating policies on how to ethically and compassionately speak with patients and families on the sensitive topic. For this, she relies heavily on her personal experience. Her father passed away from colorectal cancer in 2015.

“Every patient I consent, I feel like I am talking to my dad,” she said. “If they are with their wife, that is my mom. If I wouldn’t say it to my parents, I won’t say it.”

Nazario has put a lot of work into learning the best way to approach and consent patients, coordinate the logistics of the donation and communicate with patients’ families after death. She used surveys that were conducted with providers and patients to learn what kinds of words or phrases they wanted to hear and which ones they didn’t when talking about the program. She then created reports that would help target patients with specific genetic mutations that researchers were interested in learning more about. She makes notes on which patients are organ donors, who may be more likely to want to participate in the program. She knows how important her initial meeting with patients is.

“Some patients call me the Grim Reaper because they feel like signing up for the program is admitting the potential for death,” Nazario said. “I let them know that I am not here because we think you are going to die, or we know something you don’t. We offer this service to every patient at Moffitt whether you are doing well or poorly, and that’s when I see the anxiety leave them.”

When a patient passes away, Nazario coordinates everything to make sure the burden doesn’t land on families. She sets up transport to Moffitt for the donation and then works with the funeral home so they can begin arrangements.

The team has streamlined the process so donation and transportation to the funeral home can happen within 24 hours. The tissue collected is dispersed in three ways: some is given to the biobank, fresh tissue is taken right to the lab and then the last portion is sent to pathology for an autopsy report.

Claude Ferrari prepares samples in the tissue core lab. The Rapid Tissue Donation Program has received 60 donations since it began.

Behind the scenes, the tissue core lab processes the samples. Some parts are stained and pressed into slides for a pathologist to review before they are preserved in paraffin boxes that are refrigerated and used for research. Other parts are frozen and used for the pathologist’s report and to keep as insurance if researchers ever need more samples.

Before Nazario joined the team, the program collected 14 donations over four years. Since she joined, the program has collected 46 tissue donations in the same time period. And she has big plans to help it continue to grow.

“My ultimate goal is to do this for all cancer types. Maybe if I do a good job, it will be loud enough to make enough impact that we will continue to get funding because I really love this job,” she said.

Thanks to the program’s new grant, Nazario is now focused on building a database for all the tissue samples and research, expanding the program across Moffitt and teaching the protocol to other institutions.

The Final Gift

At Carolann Tallada’s celebration of life in January 2024, friends and family shared stories about her giving spirit — cooking meals for sick friends and leading youth classes at church. Colleagues started discussing what would later become the Carolann Tallada Sunshine Award at her school.

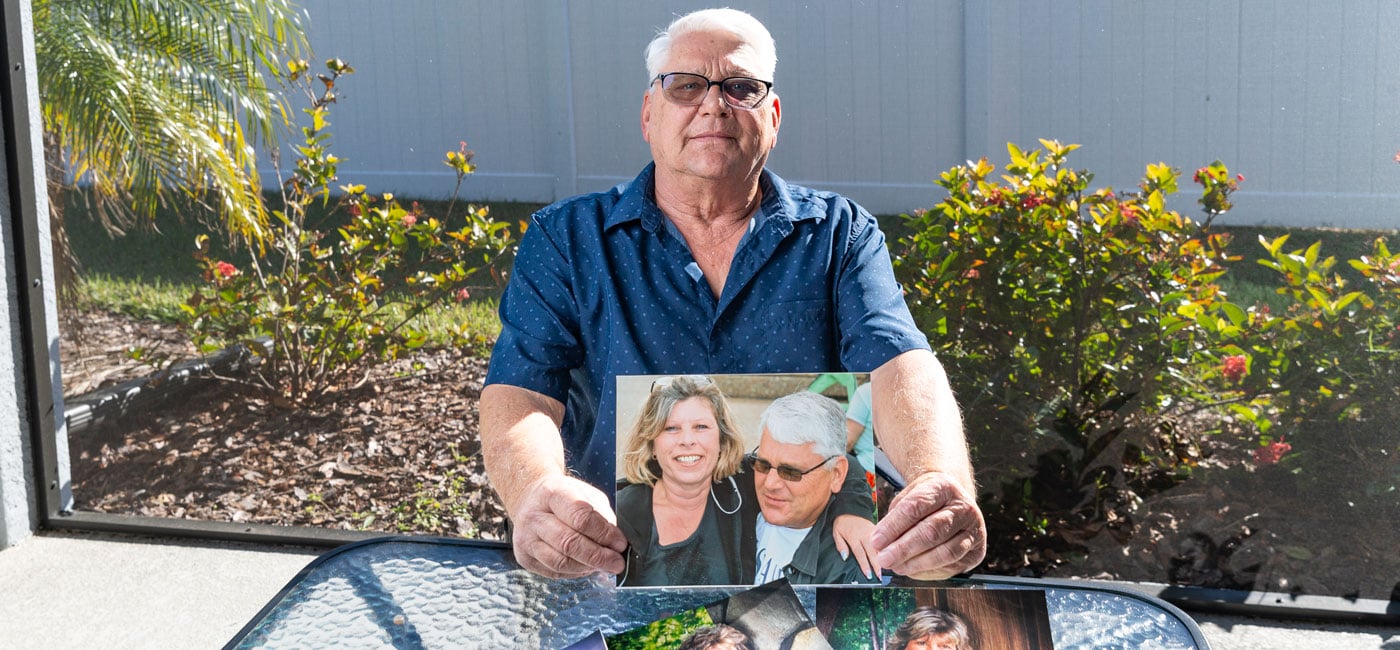

Fred Tallada hopes Carolann’s donation will provide answers and ultimately help others in the future.

No one was shocked to learn she gave one final gift just days before.

Fred Tallada hopes that gift will lead to answers to what caused his wife’s lung and adrenal cancers and why her cancer recurred after years of remission. He hopes those answers can help carry on Carolann’s legacy of helping others.

Fred was so inspired by his wife’s decision to sign up for the Rapid Tissue Donation Program that he signed up as a donor with the United Tissue Network.

“I am glad she did what she did,” he said. “Hopefully they can find a cure.”

This article originally appeared in Moffitt's Momentum magazine.