The Promise of Radiopharmaceuticals

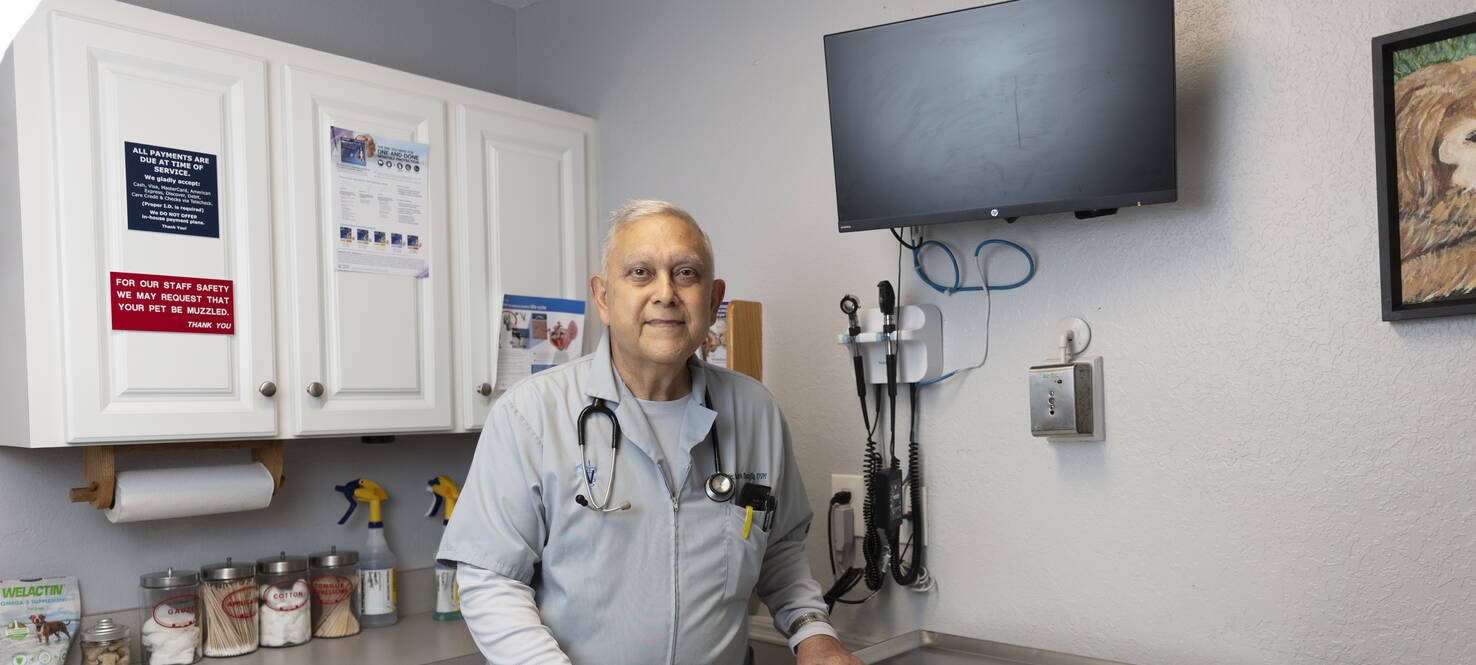

For veterinarian Norman Busciglio, life in his 50s was strong and steady. Always very active, he played golf and tennis, hosted family dinner every Sunday, grew exotic fruits and vegetables in his backyard, and rarely missed a day at his Brandon animal clinic.

Not even a prostate cancer diagnosis in 2012 at age 60 could slow him down. Despite a Gleason score of 9 — the ranking system from 2 to 10 used to grade the disease aggressiveness — Busciglio was back to normal for years after undergoing surgery, radiation and hormonal therapy.

Then in 2018, back pain led to the discovery that the prostate cancer had returned and spread to his bones. Advanced prostate cancer commonly metastasizes to the bones and leads to a poor prognosis.

“Looking at the scan, the black dots were everywhere: from the tip of my head to the tip of my toes. I said, ‘Well, it’s over. I am gone,’” Busciglio said. “I was shocked. I started making all my arrangements to die.”

Busciglio tried hormonal therapy and chemotherapy with no results. Doctors told him he was out of options, so he began researching clinical trials online. A trial in Germany caught his eye. It was using radiopharmaceuticals to deliver radiation directly to cancer cells, but it would require expensive monthslong stays overseas.

He waited. He continued to take care of animals, limiting his work to cats and dogs under 30 pounds and taking medication to temper the pulsating pain he felt in his entire body.

He kept checking for trials. In July 2019, that same radiopharmaceutical therapy became available in the United States. He picked up the phone.

“It was a long shot,” Busciglio said.

A Targeted Treatment

The field of radiopharmaceutical therapy has roots dating back to the 1940s with the use of radioactive iodine to diagnose and treat thyroid conditions. Radiopharmaceuticals are considered theranostics, a medical approach that combines diagnostic imaging and targeted therapy, leveraging the same molecular mechanism for both diagnosis and treatment.

Radiopharmaceuticals are made of two main components: a radioactive isotope that emits radiation and a pharmaceutical element that interacts with specific receptors on target cells or tissues. This combination enables radiopharmaceuticals to diagnose or treat diseases with precision.

The radioactive isotope that is used for diagnostic purposes emits radiation that can be detected to form an image. Diagnostic radiopharmaceuticals are initially used as a tool to determine if a tumor expresses specific targets. Radioactive tracers are administered to the patient before undergoing a scan to identify if the patient has the receptors needed to bind to the radiopharmaceutical treatment. The therapeutic component of radiopharmaceuticals then provides the most targeted type of treatment available.

The radiopharmaceuticals used for therapies contain a different radioactive isotope that emits ionizing radiation delivered directly to specific cancer cells while minimizing harm to surrounding healthy tissue. Most radiopharmaceuticals are delivered intravenously. The therapeutic radiopharmaceutical attaches to the diseased cell or tissue. Then the radioactive molecule undergoes radioactive decay while in the body, releasing energy in the form of radiation and killing the cancer cells.

Ghassan El-Haddad, MD, is head of the Radionuclide Therapy Program at Moffitt. He hopes the opening of Moffitt’s Speros campus in Pasco County will expand opportunities in the radiopharmaceutical field.

Some therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals emit radiation that can both destroy bad cells and form an image. This allows confirmation of where the radiopharmaceutical went, and with sequential treatments, the image can be used to monitor response. Unlike patients receiving chemotherapy who only discover the effectiveness weeks after completing treatment, radiopharmaceuticals can give patients and doctors real-time results.

“Part of the beauty of some therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals is that you can also image where the drug went,” said Ghassan El-Haddad, MD, interventional radiologist and head of the Radionuclide Therapy Program at Moffitt Cancer Center.

“Nowadays, when we are treating patients, we can scan them the next day or up to seven days later to know where the radiation went, determine how much radiation went to organs and follow them to see how the disease is evolving.”

This enables physicians to stop treatment early if the disease has completely disappeared and hold remaining doses if needed for the future. It also means they can stop treatment if it isn’t working, sparing patients from wasted time and unnecessary therapies.

“It’s an immediate feedback,” El-Haddad said. “It really is the most targeted and personalized type of treatment.”

Scientists and clinicians at Moffitt and other institutions around the world have long been working to develop and refine these targeted therapies.

In January 2018, Lutathera (lutetium Lu 177-dotatate) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of adults with somatostatin receptor-positive gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. A trial led by Jonathan Strosberg, MD, at Moffitt showed those treated with Lutathera lived substantially longer without their cancer progressing than patients treated with the standard of care. This ushered in a new generation of radiopharmaceuticals and kickstarted a decade of new radioactive treatment discovery.

In March 2022, progress in the field continued as Pluvicto was approved for treating patients with prostate-specific membrane antigen-positive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer who have been treated with novel hormonal on the VISION trial, which showed a nearly 40% reduction in the risk of death compared to standard of care alone in these patients.

It was also the trial Norman Busciglio was waiting for.

‘I Knew It Was Working’

In 2019, Busciglio saw a trial pop up online investigating a radiopharmaceutical treatment called 177-Lu-PSMA-617, which would later become Pluvicto. It was offered at Tulane University in Louisiana. Busciglio underwent diagnostic imaging, and it was determined the therapy would bind with his cells. He had his first two treatments there and transferred care to Moffitt when the cancer center opened its own arm of the trial, led by El-Haddad.

“Each scan, the bone metastases would disappear more and more,” Busciglio said. “When the pain went away after the first treatment, I knew it was working.”

Busciglio was originally diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2012. It returned in 2018, and after traditional treatments failed, he started on a radiopharmaceutical clinical trial.

Unlike his experience with chemotherapy, the treatment came with few side effects, including dry mouth and feet neuropathy.

Busciglio had six radiopharmaceutical treatments. Since then, his cancer has been stable and his prostate-specific antigen level, a figure often used to follow the evolution of prostate cancer, has been undetectable month after month for six years.

“I am on top of the world now. I don’t know how much time I have left, but I am going to enjoy it,” he said.

The now 73-year-old just celebrated 51 years of marriage and still works part time at the same veterinarian clinic he started working at 46 years ago. He and his wife have traveled to Europe a handful of times and have plans for future trips. He still hosts dinner every Sunday for his daughters and their families.

He starts every day at 5 a.m. at the gym to keep up his strength and help manage side effects from continued use of hormone medication. If his cancer returns, there is a different radiopharmaceutical drug his doctors say he can try.

“There is always hope. Never give up,” Busciglio said. “I was lucky to get this treatment, and I am still lucky to be here.”

Pushing the Research Forward

After the instrumental role Moffitt played in the approvals of Lutathera and Pluvicto, the cancer center was named a Comprehensive Radiopharmaceutical Therapy Center of Excellence by the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. Not only is Moffitt participating in multicenter radiopharmaceutical trials, but it is also working to create its own novel drugs. Developing radiopharmaceuticals is a rapidly expanding field in cancer research and treatment, and Moffitt has emerged as a leader in the space.

“Now that the field is expanding, there are multiple targets we are trying to hit,” El-Haddad said. That includes small-cell lung cancer and brain, gastric, breast and kidney cancers.

Through the research of David Morse, PhD, Moffitt has also developed its own radiopharmaceutical drug that uses Actinium-225, an alpha particle, in uveal melanoma. Alpha-emitting radionuclides can make some of the best cancer therapies due to their high amount of energy and short range. They can deliver a powerful punch to cancer cells while minimizing damage to surrounding healthy tissue.

The drug has been tested in animals and is now being tested in a phase 1 study led by Nikhil Khushalani, MD. The first-inhuman injection was performed by El-Haddad in August 2022.

“Being at an institution that bridges the gap from animal studies to first-in-human injection is truly remarkable,” El-Haddad said. “This transition showcases Moffitt’s research prowess, innovative spirit, and its commitment to advancing medical science and developing a cure for cancer.”

Moffitt also has open trials testing radiopharmaceutical drugs in neuroendocrine tumors and prostate cancer. In addition, the center has treated the first ovarian cancer patient in the U.S. with peritoneal metastases using alpha emitter Radium-224 microspheres.

The challenge moving forward is figuring out how to obtain and produce new radioactive isotopes. There are only a few alpha-emitting radioactive isotopes that have suitable half-lives to be used in the human body. A half-life is the amount of time it takes for 50% of the radioactive particles to decay. In medicine, the shorter the half-life, the better — it gives the radiopharmaceutical time to destroy the targeted cancer cells but decay before causing adverse side effects.

The availability of radioisotopes for therapeutic purposes varies. Some radioisotopes like Actinium-225 have limited production capacity, leading to supply constraints. Many therapeutic radioisotopes rely on specific research reactors or particle accelerators for production, which can be limited in number and capacity. Some radioisotopes have short half-lives, requiring rapid transportation and use, which can be logistically challenging. These factors can impact the widespread adoption and accessibility of radiopharmaceuticals, highlighting the need for increased production capacity, improved supply chain management and research into alternative production methods.

El-Haddad hopes the opening of Moffitt’s Speros campus in Pasco County will offer the space, technology and partnership opportunities to make obtaining and researching radiopharmaceuticals easier.

“We want to become a hub for radiopharmaceuticals,” he said. “We want to continue doing what we did with the Actinium-225 uveal melanoma-targeting agent with other compounds in-house at Speros.”

The goal is to continue to be a leader in nuclear oncology using radiopharmaceuticals and imaging to offer patients like Norman Busciglio the most precise and personalized treatment option.

“Even after my original diagnosis in 2012, my doctor said, ‘Norm, you have a very nasty tumor. You may live 10 years,’” Busciglio said. “They still contact me today, and I update them on how blessed I am. With new treatments being developed, long life with prostate cancer is possible to obtain.”

This article originally appeared in Moffitt's Momentum magazine.